Three reflections on Buñuel and Dali: Violence, Art and Materialism in Un Chien Andalou

"Confusion now hath made his masterpiece" - Macduff (2.3.63)

"I have striven not to laugh at human actions, not to weep at them, nor to hate them, but to understand them." - Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

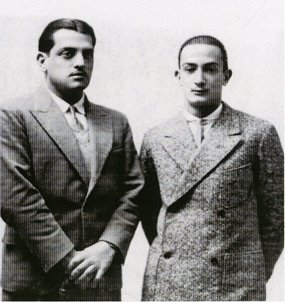

ALTHOUGH it did not provoke the anticipated riot at its 1928 premiere at Studio 28, on Montmartre, Paris, the fact that Un Chien Andalou has effortlessly courted controversy ever since will have more than compensated for any initial disappointment felt by directors Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali. That it effectively inaugurated the Surrealist genre in cinema is broadly accepted, after all, and the central objective of the production - to baffle and frustrate its audience through the absence of any coherent, defined narrative - was magnificently, if chillingly, accomplished. Inconsistencies of mood and circumstance - the opening caption "Il était une fois" ("Once Upon a Time") suggesting a fairy tale and due placidity of action, only to be followed by a moment of shocking violence and the title "Huit ans après" ("Eight years later"), with no explanation of the drama or the intervening years - contribute to a brutish demotion of linearity, the negation of any viable discourse. So dense is the allegory that even the film's most "associated" images - the slicing of an eyeball that subsequently bears no evidence of injury - are, as such, content to subvert even our most basic assumptions concerning cause and effect, subordinating biological and moral laws to a ferociously original and anarchic creativity.

The advance of our responses to the film, from an initial unease to a strained toleration of its macabre inventiveness, is effected by its paradoxes of ecstasy and pain, and the oddly benign, tantalising sense of mystery otherwise gratuitous representations engender. The film, in its perpetuation of compelling sexual and metaphysical puzzles that inexplicably excite curiosity more than revulsion, duly exploits our innate attraction to tragedy and to the fantastical. In doing so, it exposes the hypocritical sense of freedom we feel as spectators - its oddities perversely contribute to an intellectual rather than moral debate, one we openly conduct precisely because it stems from a desire to understand rather than an inclination to denounce. It is an enquiry that, as such, enables us to sidestep the suffering of those characters whose experiences pose no threat to us, and thus to privilege scrutiny over compassion. Whilst such an argument falsely supposes an entirely neutral view on our part of what befalls Andalou's protagonists, it would be nonetheless remarkable that such an entertainment could have commanded so much critical attention had we never overcome our aesthetic and ethical inhibitions in favour of a sober, "philosophical" consideration.

The advance of our responses to the film, from an initial unease to a strained toleration of its macabre inventiveness, is effected by its paradoxes of ecstasy and pain, and the oddly benign, tantalising sense of mystery otherwise gratuitous representations engender. The film, in its perpetuation of compelling sexual and metaphysical puzzles that inexplicably excite curiosity more than revulsion, duly exploits our innate attraction to tragedy and to the fantastical. In doing so, it exposes the hypocritical sense of freedom we feel as spectators - its oddities perversely contribute to an intellectual rather than moral debate, one we openly conduct precisely because it stems from a desire to understand rather than an inclination to denounce. It is an enquiry that, as such, enables us to sidestep the suffering of those characters whose experiences pose no threat to us, and thus to privilege scrutiny over compassion. Whilst such an argument falsely supposes an entirely neutral view on our part of what befalls Andalou's protagonists, it would be nonetheless remarkable that such an entertainment could have commanded so much critical attention had we never overcome our aesthetic and ethical inhibitions in favour of a sober, "philosophical" consideration.

It is the objective of what follows to offer perspectives on three key scenes in this most notorious of early experimental films - focusing on violence, art and materialism.

The object of the horror - but a victim?

WE see the face of a young female (Simone Mareuil) in close-up. The figure behind her (Buñuel) makes to slit her left eye with a razor. She half smiles, as if in stoical acceptance of the experience, making no effort to avert her suffering or to subdue her rival. She gazes at us - she cannot see him - she is emotionally and physically blind to what transpires. The woman is alarmingly indifferent to her "fate" - her coldly unemotional "response" is as unsettling as what befalls her. Her strikingly autonomous reaction is inexplicable, successively recruiting and declining our inevitable sympathy. Her neutrality stresses the curiously structured quality of the scene - the playing-out of the moment seems methodical, an enactment of demonstrative rather than spontaneous aggression. Buñuel nefariously excites our attention rather than otherwise innate revulsion. The female purportedly sanctions her violation, frustrating our inclination to condemn the savagery. Her subservience lends a horrific rationality to the action, Buñuel playfully fusing the acquiescent and the crude.

The razor scene, although according with Buñuel and Dali's creative mandate for the film, in purporting to represent a dream, is nonetheless openly sadistic and grossly unambiguous in its depiction. The woman's complicity intimates a key aspect of Kantian Moral Theory, that of Autonomy. For Kant, all we can empirically know is confined to space and time, the Sensible realm he calls the 'Phenomenal'. "True reality", though, lies beyond our apprehension, in the "Noumenal", or "Intelligible", world. Our Will is autonomous, through revealing to itself capacities for self-legislation, motivation and constraint. The Will is the noumenal "proper self" (Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals [1785] 4:461). Kant holds us to be determined through membership of the Phenomenal, free through that of the Noumenal. The Noumenal functions independently of Nature, yet grounds its laws independent of our "sensory intuition". The razor scene constitutes a dual representation - a stark metaphysics tempered by the woman's vividly-conveyed unconscious, merging the clarity of the tacit and an acutely-realised Gothic nothingness. It is the dream, the Dalian noumenal, that mitigates the woman's submissiveness, but through an appalling irony wherein hers is an ethereal rather than perceived trauma. Her Will is a terrible actualisation of Self that accepts rather than combats her plight.

Calm brutality - and the horror of the smiling complicity.

This fragment of Surrealist horror presents a figure but no character, a true Self with a redundant Agency, her volition stripped of liberty. She knows nothing of her pain, occasioned by an invisible nemesis - her fortune and pathos are by turns the greatest. Whatever the benignity of the Kantian noumenal, or the virtue of the truth revealed therein, the woman here "endures" its most depraved manifestation, an intellectual system adapted for a uniquely coarse artistic end. Such a manipulation confronts Kant with a sui generis aesthetics - experience that is not undergone in the Phenomenal, and one that the Noumenal does not accordingly rationalise.

The opening mercilessly pastiches objectivity, conveying graphically an act of bodily corruption, only to proceed immediately with new but unconnected action, offering no moral perspective on the horror just witnessed. It is a ghoulish, adamant declaration without annotation. The imagery is loaded, busy, but ideologically empty, purporting to show much but content to say nothing. The woman's "victimisation" is random but calm and explicit, momentary but neither chaotic nor frenzied. It is a beginning, but to the episodic and disparate, it can be no prologue.

Art imitating life? A conformist solitude

The woman is seated in the centre of the room, reading. The palatial, opulent interior attests to precision rather than spontaneity - there is no aesthetic approximation in her surroundings, instead an exacting decadence reflecting artistic richness but emotional coldness. Immediately conspicuous, then, is the Bourgeois immersion in the antiquated, and the perennial irony that the "freedom" of affluence can, as here, entail subjugation to inherited tastes and prescribed values. The setting ratifies her status, to be sure, but she is ensconced in a normative elegance rather than at liberty to characterise the interior with alternative or personalised motifs. Buñuel ridicules conformity to a hierarchically-stipulated aesthetic, one sympathetic to the approval of a collective rather than to individual preferences. The scene momentarily cuts to a man (Pierre Batcheff) riding along the street. Looking startled, the woman throws down the book, and goes to the window, seeing that he has fallen from his bicycle. Her book falls open at Vermeer's The Lacemaker. In discarding The Lacemaker, the woman is physically and ideologically unbound from an ordained intellectualism, humouring the precious Bourgeois aversion to the formulaic, contemporary or mainstream, that imperialistic social doctrine with which she has hitherto abided. Turning her attention from the labours of Vermeer's subject, the female overcomes the popular image of woman as creator and provider, now addressing her own desires and objectives, exercising impulses which cannot be governed or defined solely by her background or circumstances. Whatever "independence", though, in casting aside The Lacemaker, the woman now enjoys, Buñuel persistently undermined social pretension throughout his career, perhaps most abjectly in Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie (The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie) (1972), in which six characters find their dinner party interrupted by a succession of ever more surreal events. In Andalou, and in this scene, everything in the room seems generic, a rigid application of aesthetic values that cite and inspire societal acceptability. For Buñuel, the Bourgeois conception of 'beauty', and their implementation of that standard, is not an end in itself but a self-conscious reflection of social stratification, an adherence to class expectations motivated towards attainment of peer approval and potential elevation. Yet it is this, their illusory, peculiarly immature notion that exhibitions of material stability can be the measure of the individual, of their past accomplishments and of what they have to offer, that operates at the expense of the emotional, of progressive interaction. In Buñuel's philosophy, the Bourgeois outlook represents a clear yet superficial manifesto for existence, its principles, while apparently distinct and structured, little more than archaic criteria which have themselves moulded a dependence on a heavily referential framework. The Bourgeois perspective, in embracing the secondary, the manufactured, undermines the natural and the instinctual, trite salutations to an imperialistic sensibility. Idolising the grotesque - a capitalist lament? The film's attention turns from the young woman to a hermaphrodite (Fano Messan). This new character is standing in the street, a severed hand at "his" feet. "He" is surrounded by a crowd, variously compelled and bemused by what they see. A cynical Buñuel has already stressed the Bourgeois fetishism of the acquisitive, the disembodied hand becoming an object of pity. Never again will it take and keep. The crowd, transfixed by the scene, mourn for that which will no longer covet and gain. They spectate intently upon this grim curio of bodily inertia, the hermaphrodite prodding the hand with a cane as if willing it to action. A police officer holds back the crowd, then picks up the hand, places it into a box, and passes it to the "man". The mysterious figure is unresponsive, barely conscious of "his" surroundings. The crowd reluctantly disperses, leaving "him" standing alone, holding the box close to "his" chest. The hand is to be preserved as a relic of a sacred yet disappointed materialism. Once, it fostered an imperative consumerism, the necessary collation of cultural products key to inclusion within the elite. Now, it can only be a redundant emblem of a once aspirant capitalism, a flesh icon of mock happiness and enchanted but tragic fantasies. Moments later, the hermaphrodite, trance-like, is run down by an automobile. The "man" is "himself" a victim of the Bourgeois enslavement to commodities, the tragic prevalence of manufactured over intrinsic human value. |

No comments:

Post a Comment